Un’intervista profonda e introspettiva a Bendik Giske, in esclusiva per la nuova edizione di Electropark, in scena dal 10 al 13 luglio.

Electropark 2025 è alle porte, e dopo i due prologhi che hanno preso vita nel centro di Genova, dal 10 al 13 luglio inizia il Festival vero e proprio dell’edizione 2025. Un appuntamento che mette in dialogo musica elettronica, arte performativa e sperimentazione.

Ogni estate, Genova e provincia diventano il palcoscenico di una rassegna site-specific capace di attraversare club, teatri e spazi urbani, dando voce ad artisti di rilievo internazionale e realtà emergenti. L’edizione 2025 si sviluppa intorno al tema “Shared Brilliance”: un invito a immaginare la musica come pratica collettiva, esperienza sensoriale e riflessione politica.

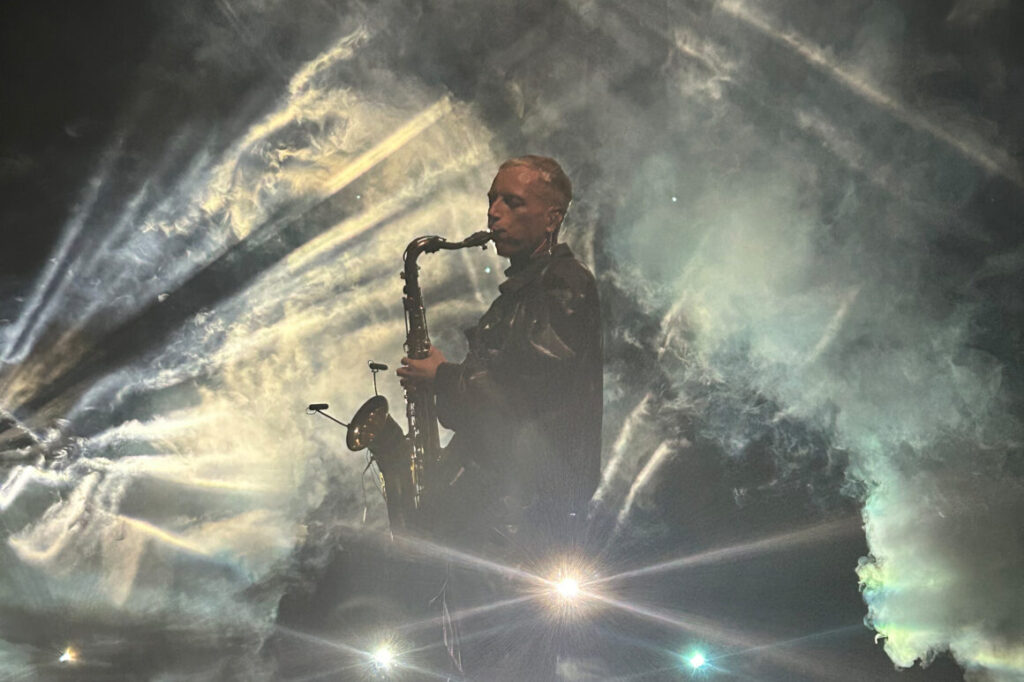

Ogni evento è unico, ogni performance rimane nella mente. Tutto è pensato in relazione allo spazio e al pubblico in una complicità continua. E in questo contesto speciale si inserisce la grande personalità e proposta di Bendik Giske, artista che fa della relazione tra corpo, suono e spazio il cuore pulsante della sua ricerca.

Il sassofono come gesto e resistenza

Originario della Norvegia e stabilitosi a Berlino, Bendik Giske è uno degli artisti più originali e riconoscibili della scena contemporanea. Sassofonista, performer e compositore, Giske ha ridefinito l’uso del proprio strumento attraverso una pratica che fonde tecnica estesa, respirazione circolare e movimento corporeo continuo. Ogni suo live è un atto fisico totalizzante, dove il confine tra performance e rituale si fa sottile. La sua musica ipnotica, vibrante e viscerale nasce dalla volontà di rimanere ancorato all’organico, anche nel cuore della contemporaneità digitale.

Dopo anni di lavoro Giske ha portato in scena un progetto solista che esalta il potere dell’effimero: nessuna scaletta preordinata, nessuna narrazione prevedibile, solo l’immediatezza dell’incontro tra artista, spazio e pubblico. I suoi dischi, tra cui “Surrender” e “Cracks”, sono stati acclamati per la capacità di rendere udibile ciò che spesso resta nascosto — come il respiro, il suono dell’ancia, l’errore.

Il lavoro di Bendik Giske inoltre è profondamente connesso alla cultura Queer, non solo per l’identità dell’artista, ma per l’approccio stesso alla performance. Ispirato dai testi dell’accademico cubano José Esteban Muñoz, Giske abita quella che viene definita “queer temporality”: un tempo non lineare, non produttivo, che sfugge alle logiche del mercato e dell’archiviazione. Le sue performance sono esperienze fugaci, non replicabili, che chiedono al pubblico di abbandonare la posizione di spettatore e diventare parte attiva del momento condiviso.

In questo senso, la sua presenza a Electropark non è solo una scelta artistica, ma anche simbolica. Difatti il Festival ha da sempre un’attenzione particolare alla comunità LGBTQIA+, e costruisce spazi in cui la diversità non è solo rappresentata, ma è parte fondante della curatela.

L’intervista:

Ciao Bendik, grazie per essere con noi.

La tua musica è profondamente radicata nel corpo — respiro, sforzo fisico e presenza. Come si evolverà questa dimensione in un contesto site-specific come quello organizzato da Electropark, in uno spazio all’aperto come la terrazza del Galata Museo del Mare?

Sarò lì con la mia “band”: Wouter Jaspers, specializzato nelle particolarità sonore del suono amplificato, e Periklis Lazarou, che si occuperà di luci e macchine del fumo. Quando suoniamo insieme, c’è sempre un elemento di jam session che prende forma. Ho difficoltà a scrivere una scaletta, perché il momento stesso richiede sempre una direzione diversa rispetto a quella che posso immaginare dietro le quinte, prima di incontrare il pubblico.

Se ci sarà un palco — e penso che ci sarà — sarò lì, con massima concentrazione, facendo del mio meglio per distribuire la mia energia fisica in modo tale da aver dato tutto entro la fine.

Electropark 2025 ruota attorno al tema “Shared Brilliance”. Quanto è importante il concetto di condivisione nella tua pratica performativa, soprattutto quando si tratta di lavorare con altri corpi, altri suoni e altre memorie?

La condivisione è tutto. Anche se passo molto tempo da solo a esercitarmi e comporre, è sempre nell’incontro con gli altri che il materiale prende vita. Non è mai qualcosa che do per scontato. Il progetto solista che porto in tour dal 2018 è quasi rimasto invisibile al pubblico per i primi dieci anni della sua ideazione. È stata, in un certo senso, un’esperienza solitaria, ma quel tempo mi ha permesso di affinare una pratica davvero mia.

Ho sviluppato un senso di appartenenza verso le intenzioni che lo alimentavano e verso le scoperte che ho fatto lungo il cammino. Il fatto che ora questo lavoro risuoni anche negli altri è qualcosa che mi sembra magico. Ho volutamente limitato al minimo le parole per descrivere questo progetto, con il desiderio che gli esiti sonori della mia esperienza possano risuonare negli altri in modo personale – un modo forse non adatto al consumo pubblico. Quando ci si riunisce in un’esperienza collettiva, possono accadere cose profonde.

Si potrebbe dire che il tuo sassofono è un’estensione di te — della tua arte e della tua mente. Pensi che la tua musica, che nasce da uno strumento tradizionale, possa essere letta come una forma di resistenza al predominio del suono puramente digitale?

È un pensiero affascinante. Per me il sassofono è uno strumento, un mezzo per acquisire conoscenza. Ho usato molti strumenti per fare musica nel corso degli anni, ma in qualche modo il sassofono è rimasto con me per oltre 30 anni, e un rapporto così lungo con uno strumento non penso di viverlo molte altre volte nella mia vita.

La mia intenzione, creando il mio progetto solista, era quella di essere libero. Di riuscire a creare qualcosa che non dipendesse da alcuna connessione, luogo, elettricità o altra infrastruttura. Certo, lavorare nell’industria musicale mi collega a tutte queste cose, ma nessuna di esse è elemento centrale del mio progetto. I momenti più significativi della mia esperienza finora sono effimeri. C’è una verità che può emergere quando possiamo semplicemente essere umani insieme, senza che tutto venga archiviato o giudicato. Forse è una forma di resistenza, io sicuramente la vedo come un’affermazione di vita libera.

Parlando di un tema che ti sta molto a cuore come la questione Queer, l’accademico cubano José Esteban Muñoz parlava di “queer time” come di un modo non lineare di abitare il tempo, oltre il qui e ora, aprendosi a futuri diversi. Nelle tue performance, quanto è importante rompere il tempo convenzionale, sovvertire i ritmi narrativi prevedibili? E cosa ti aspetti dal futuro della tua musica?

Parto dall’ultima domanda. Non ho aspettative, ma spero in una certa longevità. Ho iniziato a vedere la mia pratica come una forma di crescita in profondità, e posso osservare una chioma svilupparsi come conseguenza. Spero di raggiungere profondità che ora non riesco nemmeno a immaginare. Questo progetto è un continuo percorso di scoperta per me.

Muñoz ha ispirato me e molti altri a pensare e creare. Allontanandomi progressivamente da alcuni cliché che un tempo consideravo essenziali per fare “musica accettabile”, trovando ispirazione nei dancefloor di Berlino, mi sono chiesto in che modo quella musica giocasse con il tempo e la distribuzione dell’energia. Un tipo di musica che permette l’improvvisazione collettiva in uno spazio tridimensionale, dove l’intenzione e il desiderio umano, tra le altre cose, si esprimono attraverso il movimento.

L’effimero sembrava un elemento centrale, qualcosa di cui Muñoz parla in “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts” del 1996, dove definisce l’effimero come esperienze, gesti e momenti fugaci, intangibili, che resistono alla documentazione o all’archiviazione convenzionale. Ho preso l’idea del “là e allora”, delle possibilità che esistono oltre il momento presente, come un invito a creare qualcosa che non avevo mai suonato prima.

E rimanendo su Berlino, è la tua città adottiva — capitale della musica elettronica dagli anni ’90, casa di alcuni dei club più influenti d’Europa e oltre. Uno di questi, forse il più iconico, è il già citato Berghain. Questo luogo è stato importante anche per te e ha ispirato il tuo album Surrender (2019). Ci racconti meglio come ha preso forma questa ispirazione?

Sì, col tempo questa dichiarazione si è ridotta a “un momento al Berghain”, ma ciò che cercavo veramente di descrivere era un incontro con una cultura, avvenuto nel tempo. Il Berghain, un brand con significativi difetti, è stato solo uno dei luoghi di quell’esperienza. Penso di averne già accennato prima. Dopo quella dichiarazione, mi sono trovato a confronto con idee di cultura festaiola edonistica e della sua presunta ignoranza. Ma ciò che ho trovato erano luoghi di esperienze comunitarie effimere che favorivano una forma di trascendenza collettiva.

È stato chiaro per me che quella era la cultura alla quale volevo contribuire, decisamente non come DJ, ma per creare qualcosa che occupasse uno spazio simile. Sono diventato sempre più disilluso dall’idea del virtuoso, desiderando portare me stesso e la figura del sassofonista lontano dal solista che si vanta di “attributi” e collocarlo in un’altra posizione: quella di chi crea spazio invece di occuparlo. Mettere in scena tutto questo non è senza difficoltà, dato che lavorare nei contesti dei concerti significa perlopiù stare su un palco a mostrare abilità che coltivo da una vita, ma è un lavoro in divenire.

Sul The Guardian, John Lewis ha tracciato un ritratto molto intrigante di te: «Un sassofonista che sembra non amare il sassofono». Oltre quella che può sembrare una provocazione, Lewis ti descrive come un “Centre Pompidou sonoro”, qualcuno che porta in primo piano le imperfezioni, i difetti e le strutture interne sia dello strumento che di sé. Ti ritrovi in questa descrizione?

Mi viene da ridere a pensarci. Forse ingenuamente credevo che il fatto di suonare il sassofono da quasi tutta la vita implicasse che mi piacesse. Che eventuali critiche da parte mia fossero da intendere in quel contesto. La mia pratica nasce da decenni di studio su come gli artisti hanno usato questo strumento, e resto profondamente affascinato da questo strumento relativamente giovane. È vero che a volte mi sono sentito alienato dal ruolo che mi è stato assegnato come sassofonista, ma è più una critica alle aspettative e alle modalità di performance associate allo strumento, piuttosto che allo strumento stesso.

Mi piace molto l’analogia con il Centre Pompidou, un edificio fatto al contrario, che espone i suoi sistemi strutturali e meccanici — avrei voluto pensarci io. Una delle mie scoperte è nata dal fatto che questo progetto era solo mio, nel senso che non avevo un pubblico. Sperimentando con tecniche estese e diteggiature improbabili, sono arrivato a un materiale sonoro che si basava sulla percezione di dettagli minimi presenti nello strumento. Suoni considerati effetti collaterali, da ignorare, ma che per me sono diventati parte essenziale della mia strumentazione.

I miei primi tentativi di registrazione sono stati deludenti, perché il microfono non dava priorità agli stessi suoni che sentivo io quando suonavo da solo. Ho presentato il problema ad Amund Ulvestad, che ha poi prodotto “Surrender”, e ha ideato tecniche di microfonazione ravvicinata per, come diceva lui, registrare sezioni del suono più ampio. Questo ci ha portati su un percorso di scoperta collettiva che ha influenzato la mia esecuzione, la scrittura, la registrazione e l’amplificazione. Sì, volevo ascoltare quello che la mia amica, la compositrice Ash Fure, definisce il “ventre sonoro”. Volevo scrivere per le conseguenze non intenzionali delle mie intenzioni.

Il tuo lavoro sfuma spesso il confine tra ciò che potremmo chiamare suono puro e ciò che potrebbe essere definito rumore, glitch o imperfezione. Cosa significa per te il “difetto” nella costruzione di un linguaggio artistico?

Il motivo per cui suono come suono è che ho fallito miseramente nel diventare il sassofonista jazz che volevo essere. Forse il jazz, per come lo conoscevo e mi era stato presentato, semplicemente non era la mia musica. Quello che però ho tratto dal jazz è l’idea che tutto è possibile, e che ogni performance è un’elaborazione di quella precedente. Un difetto, un errore, un suono non intenzionale è un terreno fertilissimo per la scoperta. Ho deciso di accogliere il mio fallimento e farne qualcosa che può anche avere elementi romantici o piacevoli, ma che si muove sempre sul filo dell’errore.

Per chiudere, grazie ancora. Un’ultima domanda: se il tuo corpo è il tuo primo sintetizzatore e il respiro è il tuo beat, cosa pensi porterà via con sé il pubblico italiano da questa performance e dalla tua nuova produzione?

Permettimi di correggerti: l’ancia e la mia voce sono i miei oscillatori, il respiro è il mio riferimento per trovare il tempo. Non ho punti di riferimento esterni, devo trovare tutto dentro di me, e se qualcosa può essere il mio beat, allora sono le mie dita. Ah, e poi c’è il movimento del corpo, che nasce dai fianchi — anche lì c’è informazione ritmica e di tempo. Quando suono un pattern asimmetrico per il pubblico, evidenzio la cassa inesistente con le spalle.

Immagino che, così come il profumo è parte del gusto, il movimento possa essere parte della percezione sonora. Il pubblico italiano, finora, è stato assolutamente fantastico. Nella mia immaginazione ciò ha a che fare con l’essere cresciuti in un luogo che dà valore alla cultura e all’identità culturale (che a volte ha preso brutte pieghe, ma ha anche tanta bellezza). La mia speranza è che il pubblico di Electropark si lasci coinvolgere e si metta in gioco. Dimentichi tutto ciò che riguarda abilità o bravura, e pensi che io stia semplicemente creando uno spazio per un’ora timida — e che ciascuno, in quell’ora, sia un elemento essenziale di quello spazio.

ENGLISH VERSION

«I learned to play for what I hadn’t anticipated» Bendik Giske opens up ahead of Electropark 2025

An intimate and introspective interview with Bendik Giske, exclusively for the new edition of Electropark, taking place from July 10 to 13.

Electropark 2025 is just around the corner, and after two prologues that took place in the city center of Genova, the core of the 2025 edition kicks off from July 10 to 13. An event that brings together electronic music, performance art, and experimentation.

Every summer, Genova and its surroundings become the stage of a site-specific festival capable of crossing clubs, theatres, and urban spaces, giving voice to internationally renowned artists and emerging talents. The 2025 edition is built around the theme “Shared Brilliance”: an invitation to imagine music as a collective practice, a sensory experience, and a political reflection.

Each event is unique, each performance stays in the mind. Everything is designed in relation to space and audience, in a continuous sense of complicity. And within this special context fits the powerful presence and proposition of Bendik Giske, an artist who places the relationship between body, sound, and space at the very core of his research.

The saxophone as gesture and resistance

Originally from Norway and based in Berlin, Bendik Giske is one of the most original and recognisable artists of the contemporary scene. Saxophonist, performer, and composer, Giske has redefined the use of his instrument through a practice that merges extended techniques, circular breathing, and continuous body movement. Each of his live sets is a total physical act, where the boundary between performance and ritual becomes thin. His hypnotic, vibrant, and visceral music is born from a desire to remain rooted in the organic, even at the heart of the digital age.

After years of work, Giske has brought to the stage a solo project that celebrates the power of the ephemeral: no pre-set lists, no predictable narrative, only the immediacy of the encounter between artist, space, and audience. His records, including “Surrender” and “Cracks“, have been praised for their ability to make audible what often remains hidden — such as breath, the sound of the reed, and error.

Not only due to the artist’s identity, but also because of his very approach to performance. Inspired by the writings of Cuban academic José Esteban Muñoz, Giske inhabits what is called “queer temporality”: a non-linear, non-productive time that escapes the logic of market and archiving. His performances are fleeting, unrepeatable experiences that ask the audience to abandon the position of passive spectators and become active participants in the shared moment.

In this sense, his presence at Electropark is not just an artistic decision, but also a symbolic one. The festival has always paid special attention to the LGBTQIA+ community, creating spaces where diversity is not only represented, but is a foundational part of the curatorial vision.

The interview:

Hi Bendik, thank you for being with us.

Your music is deeply rooted in the body — breath, physical effort, and presence. How will this dimension evolve in a site-specific context like the one organized by Electropark, in an open-air space such as the Galata Museo del Mare terrace?

I’ll be there with my “band”: Wouter Jaspers on the sonic particularities of amplified sound, and Periklis Lazarou on lights and fog machines. When we play together, there’s always an element of a jam-session unfolding. I have problems with writing a set-list, as the moment always calls for another direction that what I can imagine backstage before meeting the audience.

If there’s a stage, and I think there is, I’ll be on it with deep focus doing my very best to distribute my physical energy so that I have given it all by the end.

Electropark 2025 revolves around the theme of “Shared Brilliance.” How important is the concept of sharing in your performative practice, especially when it comes to working with other bodies, other sounds, other memories?

Sharing is everything. Although I spend a lot of time alone practicing and composing, it’s always in the meeting with others that the material comes alive. It’s never something I take for granted, though. The solo project I’ve been touring since 2018 barely existed in the public realm for the first 10 years of its conception. It was in a way a lonely experience, but that time allowed me to hone a practice that was mine, I developed an ownership to the intentions that fuelled it and to the discoveries I made along the way. The fact that this work now resonates with others is like a magical feeling to me. I have deliberately kept the wording of this project to a minimum, with the wish that the sonic outcomes of my experience can resonate with others in a personal way – a way that’s perhaps not suitable for public consumption. When we gather in communal experience, profound things can happen as a consequence.

We might say your saxophone is an extension of yourself — of your art and your mind. Do you think your music, which emerges from a traditional instrument, can be interpreted as a form of resistance to the dominance of purely digital sound?

It’s an enticing thought. To me the saxophone is a tool and a vessel for acquiring knowledge. I have used many tools for music making over the years, but somehow the saxophone has remained with me for more than 30 years and that sort of experience with a tool is not something I expect to have many of in my lifetime.

My intention when creating my solo project was to be untethered. To be able to create something that does not rely on any sort of connectivity, site, electricity or any other types of infrastructure. Granted, working in the music industry connects me in all the ways mentioned, but none of it is a core element of my project. The most meaningful moments in my experience to date are ephemeral. There’s a truth that can emerge when we can just be humans together without it being archived or criticized. Perhaps it is resistance, I certainly see it as an assertion of life untethered.

Speaking of a topic you care deeply about, the Queer question, Cuban academic José Esteban Muñoz described “queer time” as a non-linear way of inhabiting time, beyond the here and now, opening up to different futures. In your performances, how important is it to break conventional time, to disrupt predictable narrative rhythms? And what do you expect from the future of your music?

Let me answer the last part first. I have no expectations, but I do hope for longevity. I’ve come to see my practice as a form of growth that goes deep, and I can observe a canopy develop as a consequence. I’m hoping to reach depths that I am currently oblivious to. This whole project is a discovery for me.

Muñoz has inspired me and many others to think and create. As I was gradually moving away from certain tropes that I had previously regarded as essential to acceptable music, finding inspiration on Berlin’s dancefloors, I found myself wondering how this music played with time and distribution of energy. A type of music that allows for communal improvisation in three-dimensional space where pure human intention and desire (among other things) comes to be expressed through movement.

Ephemerality seemed to be a central element, something Muñoz talks about in “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts” (1996), where he defines ephemera as the fleeting, intangible, and transient experiences, gestures, and moments that resist documentation or archiving in conventional ways. I took the idea of a then-and-there, possibilities that exist beyond the present moment, as a marching order to create something that I hadn’t played before.

Berlin is your adoptive city — a capital of electronic music since the 1990s, home to some of the most influential clubs in Europe and beyond. One of these, perhaps the most iconic, is Berghain. This space was also meaningful for you and inspired your album “Surrender” (2019). Can you tell us more about how that inspiration took shape?

Yeah, that statement has been distilled to refer to “a moment at Berghain” in posterity, but what I was really attempting to describe was a meeting with a culture that took place over time. Berghain, a brand with significant flaws, was only one of the sites for this experience. I believe I covered some of this in my previous answer. I have, since making this statement, been confronted with people’s ideas of hedonistic party culture and its inherent ignorance. What I found were sites for ephemeral communal experiences that facilitated collective transcendence.

The experience made it clear to me that this was the culture I wanted to contribute to, markedly not as a DJ, but to create something that held a similar space. I became increasingly disillusioned with the idea of the virtuoso, wanting to take myself and the idea of the saxophonist away from the boasting soloist with “balls” and position the saxophonist differently. As someone who holds space rather than occupies it. Now, staging this is not without it’s challenges, as working on concert arenas mostly means that I’m on stage in front of people showing off skills that I have honed for most of my life, but this is a work in progress.

In The Guardian, John Lewis painted a very intriguing portrait of you: “A saxophonist who doesn’t seem to like the saxophone very much.” Beyond what could be seen as a provocation, Lewis describes you as a “sonic Centre Pompidou,” someone who brings the imperfections, the flaws, and the internal structures of both the instrument and yourself to the forefront. Do you identify with that description?

I laugh a little when I think of this. I, perhaps naively, thought that the fact that I had played the saxophone for most of my life implied that I liked the saxophone, that any criticisms I might utter would be seen in that context. My practice comes from decades of studying what artists have used the saxophone for, and I remain deeply fascinated by this relatively young instrument. It is true that I’ve found myself alienated by the position that I as a saxophone player have been put in, but that’s more a critique of the expectations and performance of with the instrument than of the instrument itself.

I really like the Pompidou analogy, a building that’s made inside-out while exposing structural and mechanical systems, and I wish I’d thought of it myself. One of my discoveries came out of how this project was purely personal to me (as in: I had no audience for it). While experimenting with all sorts of extended techniques and improbable fingerings I slowly arrived at a material that was contingent on the audibility of minute details of sound that existed in the instrument. Sounds that were regarded as a byproducts, something to ignore, but that became an essential part of my instrumentation.

My first attempts at recording this led to profound disappointment as I discovered that the microphone failed to make the same priorities as my ears did when playing alone in a room. I presented the problem to Amund Ulvestad, who came to produce Surrender, who devised methods of close-micing the instrument to, as he put it, record sections of the larger sound. This put us on a path of collective discovery that informed both my performance, the writing, and the recording and amplification. So yeah, I wanted to listen to what my friend, composer Ash Fure, refers to as the underbelly of sound. I wanted to write for the unintended consequences of my intentions.

Your work often blurs the line between what we might call pure sound and what could be labeled noise, glitch, or imperfection. What does “flaw” mean to you in the construction of an artistic language?

The reason I play the way I do is because I failed miserably at becoming the jazz saxophonist I once set out to become. I guess jazz as I knew it, and as it was presented, just wasn’t my music to play. What I’ve taken from jazz, though, is the idea that anything is possible, and that it’s iterative in the way that each performance elaborates upon the last. A flaw, a failure, an unintended sound is very fertile soil for discovery. I decided to lean into my failure and make something that, might have romantic and pretty elements to it, but that always moved on the edge of wrong.

To close, thank you again. One last question: if your body is your first synthesizer, and breath is your beat, what do you think the Italian audience will take away from this live performance and from your new production?

Let me correct you there. The reed and my voice are my oscillators, my breath is my reference for finding tempo (I have no external reference points, I have to find all the elements of my performance within myself), and if anything is my beat it would have to be my fingers. Oh, and there’s the movement of the body, and how it stems from the hip. There’s tempo and beat information in that too. When I play an asymmetrical pattern for people, I highlight the non-existent kick-drum in my shoulders. I imagine that, like how scent is a part of flavour, movement can be a part of sonic perception. Italian audiences have, so far, been absolutely fantastic.

In my imagination it is related to growing up in a place that treasures culture and cultural identity (which definitely has gone awry at times, but there’s beauty in it too). My hope is that the Electropark audience will engage and apply themselves. Forget anything related to skill or bravura and think that I’m just holding space for a shy hour and that everyone there is an integral element to that space.