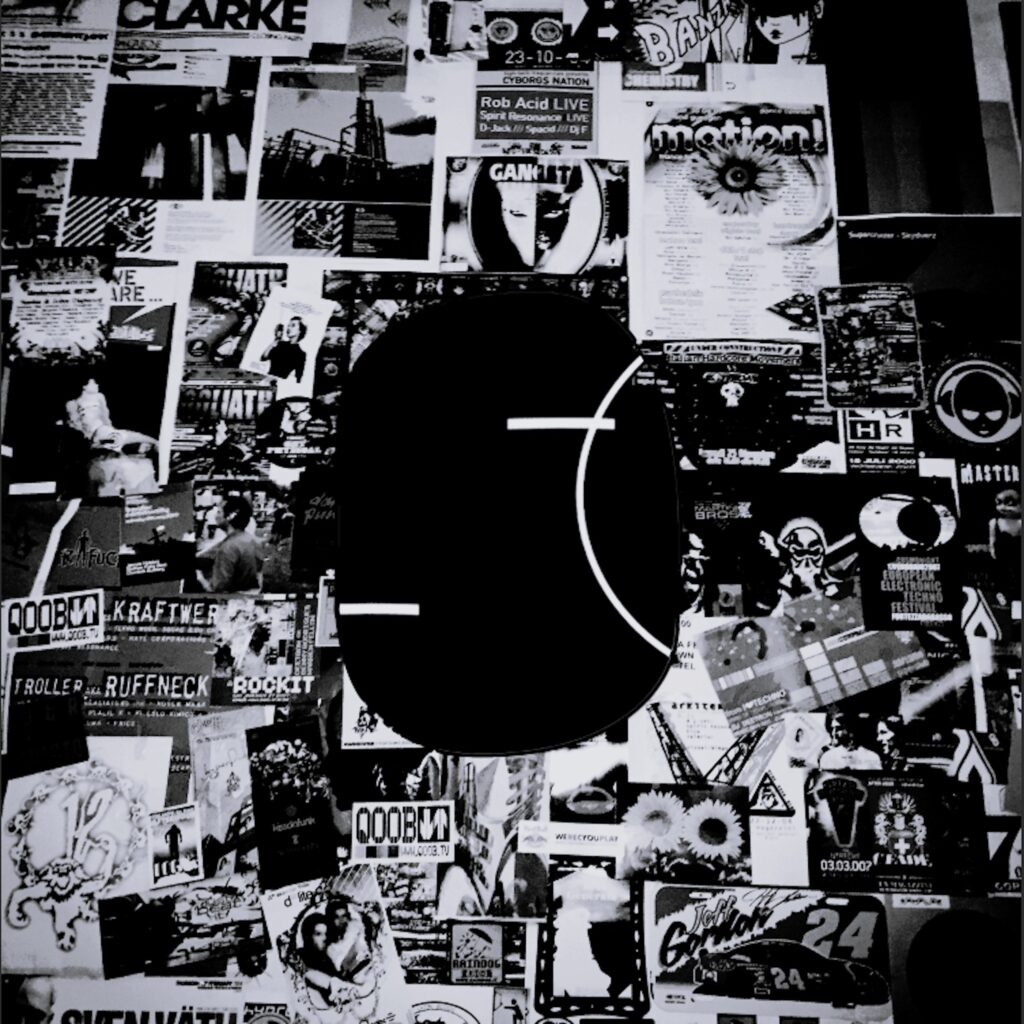

Abbiamo intervistato Edo Pietrogrande, alias P41, in occasione dell’uscita del suo ultimo album “Computer Music Before AI Supremacy” [Festina Lente]. Un lavoro che riflette sulla relazione uomo/macchina prima dell’era AI, iniziato e finito tutto su Ableton Live.

Il nuovo album di P41 è una dichiarazione di volontà provocatoria nel pieno dell’era dell’intelligenza artificiale. Sì perché Edo Pietrogrande ha voluto rivendicare un certo approccio artigianale e radicalmente umano alla produzione elettronica. Undici tracce nate e finalizzate esclusivamente al computer, senza l’uso di hardware esterni.

In un mondo sempre più dominato dalle IA la sua è resistenza in musica che si appiglia anche a ricordi emozionali e, in un certo senso, rivoluzionali provenienti dalle architetture electro di Drexciya, da Aphex Twin, dalla Warp Records.

leggi anche: “Abu Qadim Haqq, intervista senza filtri all’inventore della Techno Art”

E di certo Edo Pietrogrande, alias P41, è parte integrante di quella storia, visto che è nel settore da oltre un decennio come produttore, sound designer e ingegnere, collaborando a stretto contatto con giganti come Jeff Mills, Derrick May, Chris Liebing, Octave One, Henrik Schwarz, Francesco Tristano, solo per citarne alcuni.

Un viaggio sonoro tra techno mentale, ambient ritmica, glitch e breakbeat, che rende omaggio ai pionieri della musica elettronica con uno stile personale, cesellato, geometrico. Un lavoro che riflette sulla relazione uomo/macchina prima che l’AI diventi egemone, tra introspezione e groove, rigore e visione.

“L’AI è il dialogo che c’è in uno studio tra un produttore artistico e il suo team di compositori[…] Quindi resta la competenza ma si elimina/alleggerisce un passaggio che è l’artigianato musicale.”

– P41

Un album ricco di citazioni, con un’anima profonda che trova lo spazio per rendere onore anche due massime guide spirituali (e filosofiche) come Iannis Xenakis e John Cage.

Un album che Edo, significativamente, intitola “Computer Music Before AI Supremacy” [Festina Lente]. Un testamento sonoro per sé stesso e per tutti gli amanti della musica elettronica: per ciò che la creatività umana ha realizzato nel rapporto con macchine e numeri.

E come nel disco, l’intervista è ricca di spunti e riflessioni, anche pungenti.

Ciao Edo, è un piacere averti su Parkett. Benvenuto. Conosciamoci meglio: ci puoi raccontare da dove proviene la tua grande passione per la musica? Hai un ricordo, un momento sul quale diresti “Sì, è iniziato tutto da lì”?

Ho ricordi legati all’infanzia, il giradischi di mio padre, alcuni LP dei Beatles che ancora conservo, Luigi Tenco, bossanova a profusione, non so quante volte avrò ascoltato i cd “Girls from Ipanema” alle cene. Ho studiato chitarra dai 7 ai 10 anni, a Natale chiedevo sempre ai cugini più grandi di regalarmi cd, facevo i mixtape delle recite di ballo delle mie compagne di classe. Non c’è un momento in particolare in cui ti direi è iniziato tutto, fa parte della mia vita da sempre anche se non ho musicisti in famiglia… ho sicuramente il ricordo dell’album che mi ha sconvolto da piccolo che è una raccolta degli Art of Noise di quel genio di Trevor Horn.

È da poco uscito il tuo ultimo album “Computer Music Before AI Supremacy” [Festina Lente]. Di solito mi capita di chiedere all’artista che intervisto qual è il set up che utilizza. Ma qui mi pare di capire che l’unico strumento utilizzato sia stato il computer. O sbaglio? Ci puoi spiegare meglio in cosa è consistito il tuo lavoro.

Sì, solo computer e controller, dall’inizio alla fine, o meglio Ableton Live dall’inizio alla fine, ho voluto eliminare la distanza tra artista e artigianato, volevo essere indipendente e autonomo in tutte le fasi della produzione ed essere svincolato dall’uso di strumenti e hardware analogici. La maggior parte delle produzioni vengono fatte al computer o quantomeno impostate al computer, la mia forzatura è stata quella di non uscire mai dalla scatola dall’inizio alla fine. Ho sempre curato tutti gli aspetti delle mie produzioni, anche in passato; però spesso poi ripassavo da studio, utilizzavo il calore e la pasta di qualche synth, mi affidavo a studi di mastering per la finalizzazione (non sempre ma mi piace il workflow del disco e del supporto di orecchie fresche ed esperte all’ascolto). Qui ho voluto slegarmi da tutto e tutti e portare a termine un progetto all’interno del mio laptop.

Le trame che hai creato sono ricche di appigli emozionali, nostalgici. Ci puoi dire quali sono i tuoi riferimenti? Che probabilmente, leggendo i titoli delle tracce, non esclusivamente musicali.

È un album che ha avuto una lunga gestazione, le prime idee sono datate fine 2021 – inizio 2022. È un album più introspettivo e meno energico rispetto alle produzioni che ho finalizzato in passato. Negli ultimi due anni avevo prodotto 3 o 4 EP, una decina di tracks in tutto, e già sentivo la necessità di seguire più l’ispirazione che ostinarmi a seguire quel fiuto del dancefloor che, con gli anni, un po’ ho perso. “Computer Music Before AI” nasce per essere un omaggio a tutti i pionieri, alla ricerca, a tutti i compositori che hanno creato questo universo di suoni che ora noi chiamiamo musica elettronica: Raymond Scott, Iannis Xenakis, Delia Derbyshire, Pierre Schaeffer, Stockausen, John Cage, Luciano Berio… È un elenco infinito di maestri che con le loro intuizioni ed i loro canoni hanno creato i confini invisibili, uno spazio per una musica che prima non esisteva.

Poi ogni traccia ha la sua storia, la sua scintilla, il momento creativo in cui tutto viene naturale: quindi parto da un omaggio generale per declinarlo in diverse storie “autobiografiche”. Nei titoli c’è spesso l’ispirazione, la sintesi della storia che visualizzo nel sentire quella musica, come se fossero i capitoli di un libro, o le puntate di una serie.

“Un fenomeno come Peggy Gou non era pensabile quando io ero un ragazzino e andavo ai rave, come i Guns’n Roses o il rock epico degli anni ‘80 non sarebbero mai stati sopportati da Lester Bangs e dalla critica musicale degli anni ‘60/’70, a cui già stavano sul cazzo i Led Zeppelin per dire…”

– P41

C’è la ricerca di “Dig Deeper” ispirata dai white noise di Delia Derbyshire (una su tutte “Love Without Sound”); c’è il tema di “The Theme” ispirato dai Radiohead, con una base in stile latinoamericano come ritmo fino alla nevrosi del finale; c’è lo stile Warp / Plaid come in “Better Days”, forse la traccia la più “indie” dell’album; la scoperta con “Disclosure”, in cui apro le porte al corpo centrale del disco, dove il linguaggio tende più ai suoni rarefatti e minimali e al sound che ho ricercato tanto in questi anni, da questo punto in poi con aperture più emotive e parti più rigorose entro proprio nel mio mondo fatto di assenza, vuoti come buchi neri (“il nulla che avanza”, per citare “La Storia Infinita”) e pienissimi saturi dove non c’è più spazio per uno spillo nel mix come nell’arrangiamento.

Il titolo è tutto un programma. Semplice provocazione o manifesto di volontà? Secondo te c’è (o ci sarà) effettivamente un prima e un dopo?

È un manifesto di volontà provocatorio, quantomeno segno un punto. Ho lavorato a lungo con Alex Braga, artista e produttore che è stato tra i primi a dedicare la sua ricerca al rapporto con l’intelligenza artificiale nella produzione musicale. L’AI ormai è diffusissima a livello di artigianato musicale: doppiaggi di voci, stems, beat, basi, playlist d’ascolto e funziona spaventosamente bene. Ho voluto mettere un cue point su dove sono io adesso nell’universo musicale prima che l’intelligenza artificiale sia predominante.

Quindi, la domanda sorge spontanea: cosa ne pensi dell’intelligenza artificiale soprattutto in ambito artistico?

In un’altra intervista avevo già riportato questa storia: un mio prof. di geometria descrittiva all’università diceva sempre che se uno studente non era in grado di disegnare con la matita difficilmente sarebbe riuscito a disegnare con il computer. L’AI è più o meno la stessa cosa però siamo ad un livello ulteriore di astrazione.

Scrivere un prompt originale, dettagliato, coerente, con informazioni efficaci non è scontato se non si hanno le basi della materia per cui si utilizza. Quindi, a mio avviso, l’arte rimarrà arte perché dietro c’è un linguaggio, una conoscenza, un’esperienza pregressa che ti consente di padroneggiare un nuovo strumento altrimenti è un copiare, più o meno bene, qualcosa che esiste. E le copie sono sempre esistite e non hanno mai avuto il valore dell’originale, a parte qualche rara eccezione/abbaglio nella storia dell’arte.

Anche se ormai assodato, qualcuno potrebbe ancora sostenere/insinuare che comunque quella fatta con il pc, tramite softwere, non sia comunque musica. Così, anche se potrebbe sembrare una domanda banale, vorrei capire da te la differenza che sussiste tra ‘l’utilizzo di softwere per il computer, da parte dell’essere umano, per creare musica’ e ‘l’essere umano che si avvale dell’IA, che a sua volta sfrutta un computer, per arrivare ugualmente a creare musica?

Un po’ ho risposto sopra però, andando più nello specifico, è una differenza che si basa sul procedimento. Usare il pc significa comunque scrivere musica e utilizzare un linguaggio canonizzato di comunicazione con la macchina (note midi, velocity, note on/off, metrica divisa in bar/beat e via dicendo) che poi riprende e “semplifica” la notazione di uno spartito dando valori discreti con una precisione accuratissima a diversi parametri che in musica venivano espressi con un linguaggio comunemente utilizzato su pentagramma. A questo si aggiunge una divertentissima parte di programmazione e generazione di suoni/rumori/note basate sull’uso di cicli come LFO per creare sequenze di note, volumi, effetti trascendendo la manualità del musicista e generando dei sistemi complessi in grado di produrre composizioni controllate con una buona dose di casualità, se voluta.

L’AI è il dialogo che c’è in uno studio tra un produttore artistico e il suo team di compositori: fammi una scala maggiore di sol a 90 bpm con un beat stile “canzone di riferimento” e il testo che deve parlare di… Quindi resta la competenza ma si elimina/alleggerisce un passaggio che è l’artigianato musicale.

Ci sono, a tuo avviso, anticorpi o modi per difendersi da quello che potrebbe succedere nell’ambiente musicale con l’avvento dell’AI? O pensi che sia un processo inarrestabile, un fenomeno che diventerà diffuso ed endemico nella produzione musicale più di quanto non lo sia già oggi?

Non saprei, sicuramente è comodissima per una serie di passaggi che cominciavano ad avere costi esorbitanti. Ci siamo abituati alle royaltis da miseria nell’era di Spotify, ci abitueremo anche a questo, ma almeno questa è una rivoluzione epocale, Napster anche lo è stata, ma non è stata capita, e le discografie per correre ai ripari hanno fatto un disastro.

Il mercato discografico per come lo conoscevamo ha una storia durata neanche un secolo eppure la musica esiste da migliaia di anni. In poco più di 20 anni dall’articolo “The long tail” di Chris Anderson a oggi è successo di tutto e non ho mai pensato che si potesse tornare indietro e non sono mai stato pessimista a riguardo.

Un fenomeno come Peggy Gou non era pensabile quando io ero un ragazzino e andavo ai rave, come i Guns’n Roses o il rock epico degli anni ‘80 non sarebbero mai stati sopportati da Lester Bangs e dalla critica musicale degli anni ‘60/’70, a cui già stavano sul cazzo i Led Zeppelin per dire…

Siamo giunti praticamente al termine. Come di consueto lascio un spazio libero all’artista in cui può esprimere un suo libero pensiero o portare avanti un’istanza che ha particolarmente a cuore. Intanto io ti saluto e ti ringrazio per questa chiacchierata. Ciao!

La prima domanda dell’intervista, “tutto è inizato da lì”. Ricordarselo sempre! A chi ama la musica, a chi la fa, a chi la ascolta, a chi la organizza, a chi la insegna, a chi ne parla… la devozione e la dedizione di pensare sempre oltre ogni ostacolo, no matter what al motivo per cui siamo qui, voi, io, everybody, per dirla alla Blues Brothers.

Ho a cuore questo, a non perdere mai le energie per trasmetterlo, per ascoltare, per comporre e nel mio piccolo a condividerlo con le persone a cui riesco ad arrivare. Detta male ma detta col cuore.

ENGLISH VERSION

Interview with P41

Ciao Edo, it’s a pleasure to have you on Parkett. Welcome. Let’s get to know you better: can you tell us where your great passion for music comes from? Do you have a memory, a moment where you’d say, “Yes, it all started there”?

I have memories tied to childhood, my father’s turntable, some Beatles LPs that I still keep, Luigi Tenco, bossanova in profusion; I don’t know how many times I must have listened to “Girls from Ipanema” CDs at dinners. I studied guitar from age 7 to 10. For Christmas, I always asked my older cousins to give me CDs, and I made mixtapes for my classmates’ dance recitals. There isn’t a particular moment where I’d tell you it all started; it’s been part of my life forever, even though I don’t have musicians in my family… I definitely remember the album that blew my mind as a child: a collection by Art of Noise by that genius Trevor Horn.

Your latest album, “Computer Music Before AI Supremacy” [Festina Lente], has just been released. Usually, I ask the artist I’m interviewing about the setup they use. But here, I seem to understand that the only instrument used was the computer. Am I wrong? Can you explain in more detail what your work involved?

Yes, only computer and controller, from start to finish, or rather Ableton Live from start to finish. I wanted to eliminate the distance between artist and craft. I wanted to be independent and autonomous in all production phases and to be free from the use of analog instruments and hardware. Most productions are done on the computer or at least set up on the computer; my constraint was to never leave the box from beginning to end. I’ve always overseen all aspects of my productions, even in the past; but often then I’d go back to a studio, use the warmth and texture of some synth, or rely on mastering studios for finalization (not always, but I like the workflow of a record and the support of fresh, expert ears during listening). Here, I wanted to detach myself from everything and everyone and complete a project entirely within my laptop.

The textures you’ve created are rich in emotional, nostalgic hooks. Can you tell us about your references? Which, probably, judging by the track titles, are not exclusively musical.

It’s an album that had a long gestation period; the first ideas date back to late 2021 – early 2022. It’s a more introspective and less energetic album compared to productions I’ve finalized in the past. In the last two years, I had produced 3 or 4 EPs, about ten tracks in total, and I already felt the need to follow inspiration more than stubbornly chasing that dancefloor intuition which, over the years, I’ve somewhat lost. “Computer Music Before AI” was created as a tribute to all the pioneers, to research, to all the composers who created this universe of sounds that we now call electronic music: Raymond Scott, Iannis Xenakis, Delia Derbyshire, Pierre Schaeffer, Stockhausen, John Cage, Luciano Berio… It’s an endless list of masters who, with their intuitions and canons, created invisible boundaries, a space for music that didn’t exist before.

Then each track has its own story, its own spark, the creative moment where everything comes naturally: so I start from a general homage and then weave it into different “autobiographical” stories. The titles often contain the inspiration, the synthesis of the story I visualize when hearing that music, as if they were chapters of a book, or episodes of a series.

There’s the quest of “Dig Deeper” inspired by Delia Derbyshire‘s white noise (one standout being “Love Without Sound”); there’s the theme of “The Theme” inspired by Radiohead, with a Latin American-style rhythm as a base leading to the neurosis of the finale; there’s the Warp / Plaid style as in “Better Days”, perhaps the most “indie” track on the album; the discovery with “Disclosure”, where I open the doors to the album’s core, where the language leans more towards rarefied and minimal sounds and the sound I’ve sought so much in recent years. From this point onwards, with more emotional openings and more rigorous parts, I truly enter my world made of absence, voids like black holes (“the nothingness that advances”, to quote “The NeverEnding Story”) and saturated fulls where there’s no more room for a pin in the mix as in the arrangement.

The title says it all. Simple provocation or a statement of intent? Do you think there is (or will be) an actual before and after?

It’s a provocative statement of intent; at the very least, I’m marking a point. I worked extensively with Alex Braga, an artist and producer who was among the first to dedicate his research to the relationship with artificial intelligence in music production. AI is now widespread in musical craftsmanship: voiceovers, stems, beats, backing tracks, listening playlists, and it works frighteningly well. I wanted to put a cue point on where I am now in the musical universe before artificial intelligence becomes predominant.

So, the obvious question arises: what do you think about artificial intelligence, especially in the artistic field?

In another interview, I already shared this story: a descriptive geometry professor of mine at university always used to say that if a student wasn’t able to draw with a pencil, they would hardly be able to draw with a computer. AI is more or less the same thing, but we are at a further level of abstraction.

Writing an original, detailed, coherent, and effective prompt is not straightforward if you don’t have the foundational knowledge of the subject you’re using it for. So, in my opinion, art will remain art because behind it there’s a language, knowledge, and prior experience that allows you to master a new tool; otherwise, it’s just copying, more or less well, something that already exists. And copies have always existed and have never had the value of the original, apart from a few rare exceptions/delusions in the history of art.

Even if it’s now established, some might still argue/insinuate that music made with a PC, via software, isn’t really music. So, even if it might seem like a trivial question, I’d like to understand from you the difference between ‘the human use of computer software to create music’ and ‘the human using AI, which in turn uses a computer, to similarly create music’?

I’ve partly answered above, but, going more specifically, it’s a difference based on the process. Using a PC still means writing music and using a canonized language of communication with the machine (MIDI notes, velocity, note on/off, metric divided into bars/beats, and so on) which then takes up and “simplifies” the notation of a score, giving discrete values with extreme precision to various parameters that in music were expressed with a commonly used language on a staff. To this is added a very fun part of programming and generating sounds/noises/notes based on the use of cycles like LFOs to create sequences of notes, volumes, effects, transcending the musician’s manual skill and generating complex systems capable of producing controlled compositions with a good dose of randomness, if desired.

AI is the dialogue that takes place in a studio between an artistic producer and their team of composers: make me a G major scale at 90 bpm with a beat like “reference song” and the lyrics should be about… So the competence remains, but a step — the musical craftsmanship — is eliminated/lightened.

In your opinion, are there antidotes or ways to defend against what might happen in the music environment with the advent of AI? Or do you think it’s an unstoppable process, a phenomenon that will become widespread and endemic in music production even more than it already is today?

I don’t know; it’s certainly very convenient for a series of steps that were starting to have exorbitant costs. We’ve gotten used to paltry royalties in the Spotify era; we’ll get used to this too, but at least this is an epoch-making revolution. Napster was one too, but it wasn’t understood, and record labels made a mess trying to catch up.

The record market as we knew it has a history lasting less than a century, yet music has existed for thousands of years. In just over 20 years, from Chris Anderson’s “The Long Tail” article to today, everything has happened, and I’ve never thought we could go back, and I’ve never been pessimistic about it.

A phenomenon like Peggy Gou wasn’t conceivable when I was a kid going to raves, just as Guns ‘n Roses or the epic rock of the ’80s would never have been tolerated by Lester Bangs and music critics of the ’60s/’70s, who already couldn’t stand Led Zeppelin, for example…

We’ve pretty much reached the end. As usual, I’ll leave a blank space for the artist where you can express a free thought or bring up an issue you particularly care about. Meanwhile, I’ll say goodbye and thank you for this chat. Ciao!

The first question of the interview, “it all started there”. Always remember that! To those who love music, to those who make it, to those who listen to it, to those who organize it, to those who teach it, to those who talk about it… the devotion and dedication to always think beyond every obstacle, no matter what, to the reason why we are here, you, me, everybody, to put it like the Blues Brothers.

This is what I care about: never losing the energy to convey it, to listen, to compose, and in my small way, to share it with the people I manage to reach. Poorly put, but said from the heart.