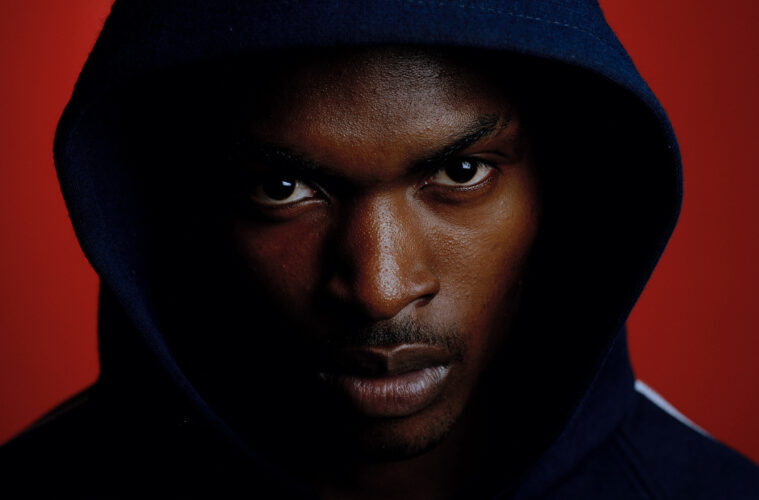

Actress si racconta in un’intervista esclusiva su Parkett in occasione della Biennale Musica di Venezia.

Actress, al secolo Darren J. Cunningham, è sicuramente una delle figure più influenti e visionarie della musica elettronica contemporanea. Nato nelle Midlands inglesi, dove la prima passione per il calcio fu interrotta da un infortunio, Cunningham si è immerso nella musica con la stessa determinazione con cui un atleta affronta una partita.

La sua educazione musicale, unita a una curiosità vorace per le culture sonore – dai pionieri della techno di Detroit alle sperimentazioni orchestrali, ha plasmato una visione artistica in cui ogni suono è un atto di riflessione e ogni progetto un ecosistema a sé stante.Dall’esordio con “Hazyville” alla svolta di “Splazsh“, dalle meditazioni oscure di “Ghettoville” fino alle rielaborazioni di Stockhausen e agli esperimenti orchestrali di LAGEOS, la sua carriera non è mai stata un semplice susseguirsi di album, ma la creazione di una storia artistica assolutamente irripetibile.

Le collaborazioni globali, da Londra a Kinshasa, dal Rajasthan ai palazzi brutalisti del Barbican, e l’uso pionieristico di intelligenze artificiali, dimostrano come la sua arte sia sempre aperta al dialogo, capace di trasformare strumenti e tecnologie in estensioni di un pensiero creativo fluido e radicale.

Alla Biennale di Venezia, luogo di riflessione e confronto tra sensibilità e idee, Parkett Channel ha incontrato Actress per discutere la sua arte in relazione alla vita: la paternità come lente della creatività, l’intelligenza artificiale come partner di sperimentazione, il simbolismo dietro l’ amato numero 88, e la capacità degli spazi artistici di generare speranza, nutrire la comunità e far germogliare nuove possibilità.

In ogni parola, la visione di Cunningham appare chiara: la musica e l’arte non sono mai fini a sé stesse, ma strumenti per esplorare, comprendere e riscrivere il mondo intorno a noi. Buona lettura!

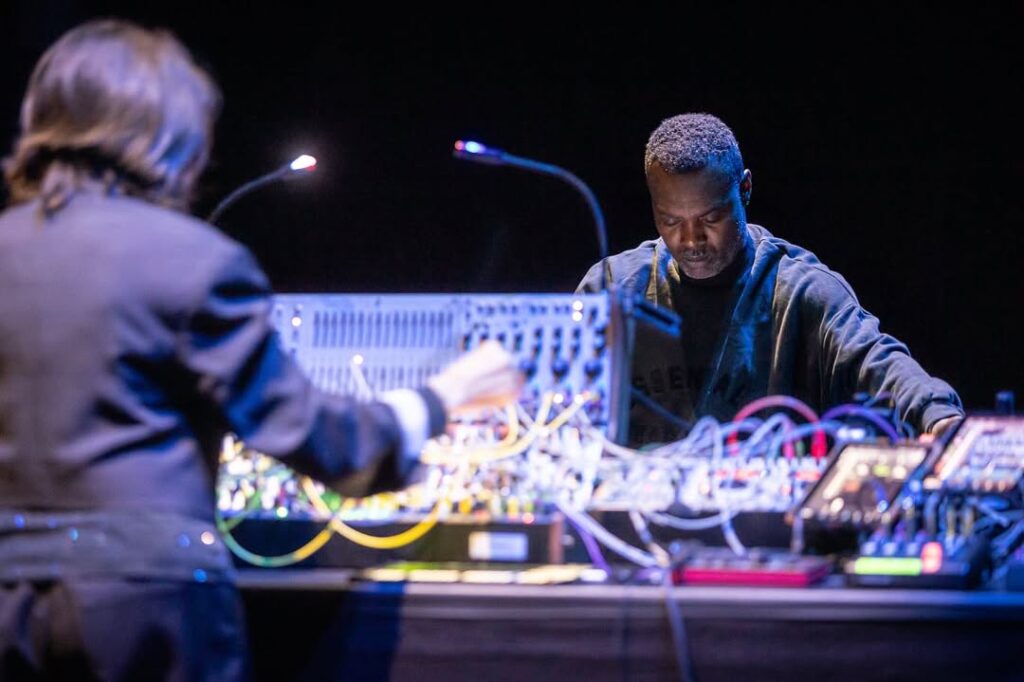

Ciao Actress, benvenuto su Parkett e grazie di essere qui con noi. Ci troviamo qui alla Biennale della Musica di Venezia, dopo la tua performance con Suzanne Ciani al Teatro alle Tese di Venezia. Grazie davvero di essere qui.

È davvero un piacere per me.

Per iniziare vorrei partire da una considerazione interessante che ho letto in molte tue interviste sul tuo rapporto con la solitudine e i tuoi rituali creativi. Arrivando in una città come Venezia, circondata dall’acqua e dal silenzio, un luogo decisamente particolare oltre che bellissimo, riesci a trovare lo stesso spazio di riflessione e creativo?

Sai, ogni volta che viaggio è sempre un po’ spaesante. Essere in un posto circondato dall’acqua, dove l’intero tema della città è l’acqua, costruisce un’ occasione unica per entrare in questo spazio anche a livello mentale.

A Londra vivo vicino al Tamigi, quindi mi piace stare accanto all’acqua. Credo sia il mio lato Scorpione che ne ha bisogno. Mi piacciono molto anche i canali: nelle Midlands, da dove provengo, siamo circondati da un fitto sistema di canali, un retaggio della Rivoluzione Industriale, quindi con un’atmosfera un po’ più industriale.Amo visitare città come Amsterdam e passeggiare lungo i canali. Per questo trovo tutto ciò molto bello. Ieri però sono arrivato piuttosto tardi e non sapevo bene cosa aspettarmi. Ho viaggiato tantissimo in Europa e nel resto del mondo, ma non ero mai stato a Venezia. È stata la mia prima volta, e ho provato una sensazione nuova: dopo anni di viaggi, ho riscoperto una freschezza e un entusiasmo davvero piacevoli. Mi ha fatto molto bene.

Arrivare dall’aeroporto in taxi d’acqua è stato entusiasmante, surreale e un po’ spaventoso allo stesso tempo, ma anche molto divertente. Davvero un bell’inizio. Ho avuto anche un po’ di tempo per una passeggiata: mi piace camminare, perdermi e riflettere. Ho trovato qualche buon momento per farlo con calma, e la giornata era splendida e soleggiata. Molto piacevole.

Credo che a livello personale la paternità sia diventata un tema ricorrente nella tua vita e nel tuo modo di vedere il mondo.Come ti ha cambiato a livello artistico essere padre?

Mi hanno cambiato profondamente. I miei figli significano tutto per me e credo che la vera trasformazione sia avvenuta nel mio modo di lavorare in studio. Un tempo ero molto frenetico, persino caotico, soprattutto da giovane: mettevo le mani ovunque, mi buttavo su tutto senza pensarci troppo.Col tempo, già prima di diventare padre, ho iniziato a rallentare e a capire meglio l’ambiente che avevo costruito: ero partito con una sola macchina e mi ero ritrovato con una moltitudine di dispositivi, una sorta di piccola metropoli fatta di reti e mappe mentali.

Ma con l’arrivo dei figli ho cambiato ancora di più: quando siamo insieme, lavoro pochissimo. Uso quel tempo per stare davvero con loro.Mia figlia, in particolare, è affascinata da manopole e interruttori: le adora. Anche mio figlio è interessato, ma in modo più discreto. È più un giocatore, e ora che cresce tiene molto alla sua privacy. Quando vuole stare per conto suo sparisce nel mio studio: credo che il rumore elettronico di fondo, morbido e oscillante, sia per lui una sorta di rifugio sicuro.È qualcosa di molto tenero. Avere figli è davvero un dono meraviglioso. Hanno influenzato la mia musica, non tanto nelle idee, forse, quanto nel modo in cui mi avvicino alla musica e nel modo in cui penso al farla.

A proposito di gaming, in uno dei tuoi ultimi album, “88”, fai riferimento al gioco e usi la teoria dei giochi come struttura. C’è qualcosa di infantile, quasi magico, in questo approccio all’esplorazione. Quanto è importante per te restare connesso al lato ludico della creazione?

È molto importante, perché i miei primi lavori erano più concentrati sull’estrarre contenuti emotivi, su ciò che avevo interiorizzato dalle mie esperienze: le perdite, la famiglia, il lasciare casa, il trasferimento in una grande metropoli come Londra. All’epoca la mia musica aveva un carattere molto più esistenziale.

A un certo punto, però, nella creatività arriva il momento in cui devi trovare nuovi modi per stimolare il processo artistico. E quale modo migliore se non introdurre elementi di gioco nella creazione musicale? In fondo, se ci pensiamo, gran parte dell’informatica e della computer science si basa sulla teoria dei giochi.Non è un approccio che utilizzo sempre, ma per alcuni album, in particolare “88”, è stato il punto di partenza per progettare nuova musica.

Usi otto computer nel tuo studio, ciascuno con un nome proprio, quasi come fosse una rete di entità viventi. Vedi il tuo studio più come un’estensione della tua mente o come un ecosistema in cui sei solo uno degli elementi?

Direi entrambi. È sicuramente un’estensione della mia mente: otto computer che fanno cose diverse e custodiscono molto materiale d’archivio. Il mio studio è organizzato così: ho una postazione dedicata a R.I.P., una a Splash, una a Ghettoville, Karma & Desire e agli altri dischi.Quando decido, ad esempio, di lavorare a una seconda versione di R.I.P., so esattamente su quale postazione andare.

A volte queste stazioni vengono collegate tra loro. In ogni caso, sono tutte sincronizzate sullo stesso clock.Appena premo un pulsante su un laptop, si accendono luci ovunque: è davvero come se fosse un’estensione della mia mente. Ma allo stesso tempo è un ecosistema estremamente complesso. Non rimane mai uguale. Cambio continuamente le connessioni, ricostruisco tutto in modi diversi. Ogni volta il linguaggio cambia. Cerco di mantenerlo in costante flusso.

Recentemente hai collaborato con YoungPaint, un’entità musicale basata sull’intelligenza artificiale. Qual è oggi la tua relazione con l’IA? La vedi più come una sfida intellettuale, un partner creativo o una lente attraverso cui osservare l’evoluzione umana?

È cambiata. A volte l’IA può funzionare come una sorta di proxy, altre volte come un diversivo. Ma il contesto emotivo resta sempre umano: un computer non può generare emozione senza un input umano. Lo abbiamo visto anche stasera, giusto?Può funzionare in modi diversi, dipende da come la si vuole utilizzare. Io la uso raramente per dirigere qualcosa in modo strettamente algoritmico. YoungPaint, certo, era molto più basato su decisioni algoritmiche. Oggi invece la impiego soprattutto così: quando ho un suono, un’idea o una direzione, uso l’IA per farmi suggerire possibilità. Guardo le idee che propone, ne scelgo una e la unisco con un’altra.

Se utilizzo l’intelligenza artificiale, che ormai è uno strumento creativo molto diffuso e commerciale, lo faccio in questo senso, non per lasciare che prenda il controllo o per partire da ciò che decide lei. C’è sempre un elemento umano di guida. E, se devo essere sincero, non credo che arriverà mai un momento in cui sarà diverso. In fondo, come esseri umani siamo già “artificialmente intelligenti”: tutto nasce dall’interazione neurale umana. Devo comunque sedermi a una drum machine e programmarla. Devo comunque mettermi davanti a un sintetizzatore e suonarlo.Amo l’estetica degli strumenti elettronici, e adoro passare il tempo su eBay a cercare quale sintetizzatore comprare dopo. Questo non ha nulla a che fare con l’IA. Amo semplicemente fare musica elettronica, davvero.

Ritorniamo un secondo su “88”. Te lo sei tatuato sulle mani.Sappiamo che è un simbolo potente, rappresenta l’infinito ma anche la dualità. Come si collega l’idea di infinito alla tua spinta a non smettere mai di fare musica?

È tutto ciò che hai detto, ma è anche legato ai punti di ritorno. Mi sono reso conto che, da quando ho iniziato a fare musica fino a oggi, ho compiuto più volte una sorta di figura a otto, tornando ciclicamente al punto di partenza.Ci sono stati momenti in cui, ad esempio, ho rivoluzionato completamente il mio studio e poi ho passato anni a produrre pochissima musica, dedicandomi quasi solo alla lettura di manuali. A volte può essere scoraggiante, perché vorresti creare, ma capisci che devi tornare all’inizio e quasi reimparare tutto, soprattutto se vuoi accendere una nuova scintilla creativa, cosa che si collega anche a ciò che dicevi riguardo ai miei figli e a ciò che desidero lasciare loro.

Vedo gran parte del mio lavoro, praticamente tutto, come asset sonori, proprietà intellettuali sonore. Sono i miei asset tangibili, se vogliamo guardare la cosa in modo capitalistico. È ciò che vorrei lasciare ai miei figli, sperando che abbia valore, non solo commerciale, ma anche umano, che possa toccare e ispirare le persone, incoraggiarle a fare musica, e allo stesso tempo ispirare i miei figli a essere creativi e a capire che ci sono sempre nuovi limiti da superare.

Hai iniziato con la tecnologia sull’Amstrad CPC-464 e oggi sei considerato uno degli artisti più concettuali della musica elettronica. Cosa ti ha affascinato per primo della tecnologia e cosa continua ancora a sorprenderti?

Per me, in realtà, non è iniziato con la tecnologia: è iniziato costruendo cose. Da bambino ero molto preso dal Meccano, mi piaceva assemblare, seguire le istruzioni. Ero un po’ perfezionista: volevo che tutto fosse fatto bene, con la giusta prospettiva. E più ascoltavo musica e capivo come altri spingessero i limiti della tecnologia, più mi chiedevo: “Come lo hanno fatto? Cosa serve per ottenere questo suono?” Piano piano ho trovato la mia strada, e quando è successo è stato tutto naturale.

Appena mi sono seduto davanti a una drum machine, appena sono entrato nel mondo dell’elaborazione del suono, è venuto tutto spontaneo. Quasi automatico, davvero. E quella fascinazione non mi ha mai lasciato. Sono sempre stato appassionato di computer.

Come hai ricordato, il 464 è stato il mio primo computer “vero”, poi è arrivato il PC, e infine un laptop con un programma di editing molto semplice.Facevo beat senza neppure una timeline, solo tagliando e incollando suoni. Poi sono arrivati software come Reason e Ableton, che mi hanno permesso di unire davvero le idee. Da lì è cambiato tutto.E devo ringraziare molte persone. Gente come Robert Henke di Ableton, con capacità enormemente superiori alle mie, che ha creato quel software. Ha rivoluzionato il modo in cui facciamo musica oggi. Sono grato a queste persone.

Hai detto una volta che il caos può essere positivo. Citando Kandinsky: come gestisci l’equilibrio tra caos creativo e disciplina tecnica nella tua pratica quotidiana in studio?

Con l’età, e per proteggere facoltà come l’udito, devi essere più misurato nel tempo che passi a lavorare. Ci sono stati periodi in cui, soprattutto quando fumavo molto, mi svegliavo, andavo dritto in studio e fumavo, fumavo, fumavo. Ero molto più disconnesso dalla realtà, a essere sincero.Crescendo,e soprattutto con i figli, non puoi più vivere così. Devi trovare dei modi per…Bilanciare.Esatto, per bilanciare. Allo stesso tempo, però, conservo moltissime informazioni nella mia testa. Passo molto tempo ad accumularle e, quando arriva il momento di metterle in pratica, vado in studio e so esattamente cosa fare. Inoltre prendo molti appunti: disegno piccoli diagrammi, idee, scale, qualunque cosa mi passi per la mente.

Molte volte vado in studio e in realtà non creo nulla di compiuto. Sto lì a fare “du-du-du-du-du” sul sequencer, poi lo faccio partire, registro qualcosa, lo lascio lì, ci torno più tardi e aggiungo un altro livello. Costruisco strati nel tempo.Poi prendo un computer, magari una tastiera MIDI, e mi concedo una pausa ad Amsterdam per un paio di giorni: porto con me tutto il materiale registrato e lì comincio davvero a scrivere. Oggi scrittura e registrazione sono molto separate, mentre prima erano fuse, un tutt’uno. Ora invece prima scrivo e poi registro. E questo è il processo attuale.

Il tuo suono è sempre stato misterioso e astratto, ma mai freddo. Come mantieni emozione e calore in paesaggi sonori così digitali e geometrici?

Bhe… è difficile.Se devo essere sincero, ho sempre amato ogni tipo di musica. Da giovane ero molto orientato verso soul, R&B, e naturalmente il pop. Suonavo il clarinetto, quindi ascoltavo davvero di tutto: non chiudevo mai le orecchie a nulla, non snobbavo nessun genere.Credo che questo abbia creato dentro di me una sorta di libreria interna di suoni e melodie. Ho tantissime melodie in testa, prese da mille dischi.

Ma quando emergono, vengono processate attraverso un filtro interno e trasformate in qualcosa di completamente diverso.Sì, la mia musica può sembrare misteriosa, ma per me è solo uno specchio della mia vita quotidiana, del mio stato di coscienza. A me non sembra misteriosa. Capisco però perché lo sembri agli altri. E non ho mai voluto fare musica di genere.Amo la drum and bass, ma non ho mai voluto farla. Amo la jungle, ma non ho mai voluto fare jungle. Amo la techno, ma non ho mai voluto fare solo techno.

Ho sempre voluto un linguaggio mio. Che sia duro, bello o astratto, deve comunque far provare qualcosa — anche a me. Quando succede, allora posso lasciarlo andare.Sono fortunato perché ho molta musica che la gente non ha ancora ascoltato: album che io stesso ho potuto vivere e riascoltare per anni prima che uscissero. Quindi quando pubblico qualcosa è perché ci ho convissuto a lungo e sento che è il momento giusto. Voglio rilasciare musica che risuoni con me.Se poi piace anche agli altri, fantastico.

Ultima domanda.La Biennale spesso porta temi come identità futura, crisi e speranza. Qual è oggi la tua più grande speranza? Non solo come artista, ma come essere umano che crea, guida ed evolve in questo mondo?

Ci sono stati molti momenti in cui la musica mi ha davvero salvato. Quando attraversavo periodi difficili, c’era sempre un brano in grado di aiutarmi a superare la situazione o a colmare un vuoto. Quando il mondo è teso, trovo rifugio nella musica. Sono fortunato ad averla come canale emotivo.Ed è questo che considero importante nella musica elettronica moderna. Credo che oggi così tante persone facciano musica perché hanno bisogno di un luogo dove appendere le proprie emozioni, le proprie domande, le proprie filosofie. E molto di tutto questo lo ritrovi creando suoni e toni.Il mondo è sempre stato un posto complicato, ma anche meraviglioso. Sono sempre grato di poterlo vivere, davvero.

Per quanto riguarda la politica e le tensioni, forze che incombono costantemente su di noi, è proprio per questo che esistono i club. È per questo che esistono luoghi come la Biennale, dove possiamo osservare idee sul futuro.Ed è lì che risiede la speranza. Finché avremo spazi per la discussione, l’arte e la creatività, andrà tutto bene. La tecnologia continuerà ad avanzare e a cambiarci. Ci saranno sempre menti brillanti, menti benevole e menti meno benevole; ma è sempre una danza, un gioco di spinte e controspinte. È sempre stato così, e deve essere così.E in questo c’è sempre speranza. È lì che faccio atterrare il mio aereo.Molto realistico.

Grazie, Actress , per essere stato con noi. Buona serata a Venezia e a presto.

È stato un vero piacere,Grazie mille.

ENGLISH VERSION

Actress opens up in an exclusive Parkett interview on the occasion of the Venice Music Biennale.

Actress, born Darren J. Cunningham, is undoubtedly one of the most influential and visionary figures in contemporary electronic music. Growing up in the English Midlands, where his first passion for football was cut short by an injury, Cunningham immersed himself in music with the same determination an athlete brings to the game.

His musical upbringing, combined with a voracious curiosity for sound cultures, from the pioneers of Detroit techno to orchestral experimentation, has shaped an artistic vision in which every sound is an act of reflection and every project an ecosystem unto itself. From his debut “Hazyville“to the breakthrough of “Splazsh“, from the dark meditations of “Ghettoville” to reworkings of Stockhausen and the orchestral experiments of LAGEOS, his career has never been a mere sequence of albums, but the creation of a truly singular artistic narrative.

Global collaborations, from London to Kinshasa, the deserts of Rajasthan to the brutalist halls of the Barbican, and his pioneering use of artificial intelligence demonstrate how his art remains open to dialogue, transforming instruments and technologies into extensions of a fluid, radical creative thought.

At the Venice Biennale, a space for reflection and exchange between sensibilities and ideas, Parkett Channel met Actress to discuss his art in relation to life: fatherhood as a lens on creativity, artificial intelligence as a partner in experimentation, the symbolism behind the cherished number 88, and the capacity of artistic spaces to generate hope, nurture community, and cultivate new possibilities.

Through every word, Cunningham’s vision comes into focus: music and art are never ends in themselves, but tools to explore, understand, and rewrite the world around us. Enjoy the read!

Hi Actress, welcome to Parkett and thank you for being here with us. We’re here at the Venice Music Biennale, right after your performance with Suzanne Ciani at the Teatro alle Tese in Venice. Thank you so much for joining us

It’s truly a pleasure for me.

To start, I’d like to pick up on an interesting point I’ve read in many of your interviews about your relationship with solitude and your creative rituals. Coming to a city like Venice, surrounded by water and silence—a truly unique and beautiful place—do you find the same space for reflection and creativity?

You know, every time I travel it’s always a little disorienting. Being somewhere surrounded by water, where the entire city is defined by it, creates a unique opportunity to enter that space, even mentally.In London, I live near the Thames, so I like being close to water. I think it’s my Scorpio side that needs it. I also really like canals: in the Midlands, where I’m from, we’re surrounded by a dense network of canals—a legacy of the Industrial Revolution, so with a somewhat more industrial feel. I love visiting cities like Amsterdam and walking along the canals. That’s why I find all of this so beautiful.

Yesterday, though, I arrived quite late and didn’t really know what to expect. I’ve traveled extensively across Europe and the world, but I had never been to Venice. It was my first time, and I felt something new: after years of traveling, I rediscovered a sense of freshness and real enthusiasm. It felt very good.Arriving at the airport by water taxi was thrilling, surreal, and a little scary at the same time, but also a lot of fun. Really a great start. I also had a bit of time to take a walk: I enjoy wandering, getting a little lost, and reflecting. I had some good moments to do that at my own pace, and it was a beautiful, sunny day. Very pleasant.

I believe that fatherhood has become a recurring theme in your life and your way of seeing the world. How has being a parent changed you artistically?

It has changed me profoundly. My children mean everything to me, and I think the real transformation happened in how I work in the studio. I used to be very frenetic, even chaotic, especially when I was younger: I had my hands in everything, diving into projects without thinking too much.

Over time, already before becoming a parent i started to slow down and understand better the environment I had built: I started with just one machine and ended up with a multitude of devices, a kind of small metropolis of networks and mental maps.But with my children, things changed even more: when we’re together, I rarely work. I use that time to really be with them.My

My daughter, in particular, is fascinated by knobs and switches, she absolutely loves them. My son is also interested, but more quietly. He’s more of a gamer, and now that he’s growing up, he values his privacy. When he wants his own space, he disappears into my studio; I think the soft, undulating electronic background noise is a kind of safe haven for him.It’s very sweet. Having children is truly a wonderful gift. They’ve influenced my music, not so much in terms of ideas, perhaps, but in how I approach music and how I think about making it.

Regarding gaming, in one of your recent albums, 88, you reference games and use game theory as a structural framework. There’s something almost childlike, even magical, in this approach to exploration. How important is it for you to stay connected to the playful side of creation?

It’s very important, because my early work was more focused on drawing out emotional content, what I had internalized from my experiences: loss, family, leaving home, moving to a big city like London. At that time, my music had a much more existential character.At some point, though, in the creative process, you reach a moment when you need to find new ways to stimulate your artistic output. And what better way than to introduce elements of play into music-making?

If you think about it, a lot of computer science is based on game theory.It’s not an approach I use all the time, but for certain albums, particularly “88”, it was the starting point for designing new music.

You use eight computers in your studio, each with its own name, almost like a network of living entities. Do you see your studio more as an extension of your mind or as an ecosystem in which you’re just one element?

I’d say both. It’s definitely an extension of my mind: eight computers doing different things, holding a lot of archival material. My studio is organized like this: I have one workstation dedicated to R.I.P., one for Splash, one for Ghettoville, Karma & Desire, and the other albums.When I decide, for example, to work on a second version of R.I.P., I know exactly which station to go to. Sometimes these stations are linked together. In any case, they’re all synchronized to the same clock.

As soon as I press a button on a laptop, lights turn on everywhere—it really feels like an extension of my mind. But at the same time, it’s an extremely complex ecosystem. It’s never static. I’m constantly changing the connections, rearranging everything in different ways. Every time the “language” changes. I try to keep it in a constant state of flow.

Recently you collaborated with YoungPaint, an AI‑based musical entity. What is your relationship with AI today? Do you see it more as an intellectual challenge, a creative partner, or a lens through which to observe human evolution?

It has changed. Sometimes AI can act as a kind of proxy, other times as a distraction. But the emotional context is always human: a computer can’t generate emotion without human input. We saw that tonight, right?It can work in different ways, depending on how you want to use it. I rarely use it to direct something in a strictly algorithmic way. YoungPaint, of course, was much more based on algorithmic decision‑making.

Today, though, I mostly use it like this: when I have a sound, an idea, or a direction, I use AI to suggest possibilities. I look at the ideas it offers, pick one, and merge it with another.If I use artificial intelligence—which by now is a very common and commercial creative tool—I use it in that sense, not to let it take control or to start from whatever it decides. There’s always a human guiding element. And, to be honest, I don’t think there will ever be a moment when it’s different.At the end of the day, as human beings we’re already “artificially intelligent”: everything starts from human neural interaction. I still have to sit down at a drum machine and program it. I still have to sit at a synthesizer and play it.I love the aesthetic of electronic equipment, and I love spending time on eBay searching for which synthesizer to buy next. That has nothing to do with AI. I simply love making electronic music, truly.

Let’s go back for a second to “88.” You tattooed it on your hands. We know it’s a powerful symbol—it represents infinity, but also duality. How does the idea of infinity connect to your drive to never stop making music?

It’s everything you said, but it’s also linked to the idea of returning. I realized that, from the moment I started making music until today, I’ve traced this kind of figure-eight pattern multiple times, cycling back to where I started. There have been moments when, for example, I completely overhauled my studio, and then spent years producing very little music, almost solely focused on reading manuals. Sometimes it can be discouraging, because you want to create, but you understand that you have to go back to the beginning and almost relearn everything, especially if you want to spark a new creative flame.

This also ties into what you mentioned about my children and what I hope to leave for them.I see a large part of my work, practically all of it, as sound assets, as intellectual property in the form of sound. They are my tangible assets, if we want to look at it in a capitalist way. It’s what I hope to leave my children, hoping it has value, not just commercial value, but human value; that it can touch and inspire people, encourage them to make music, and at the same time inspire my children to be creative and to understand that there are always new limits to push beyond.

You started with technology on the Amstrad CPC-464, and today you’re considered one of the most conceptual artists in electronic music. What first fascinated you about technology, and what still surprises you?

For me, it didn’t really start with technology, it started with building things. As a kid, I was really into Meccano; I loved assembling things, following instructions. I was a bit of a perfectionist: I wanted everything to be done right, with the correct perspective. And the more I listened to music and understood how others were pushing the limits of technology, the more I asked myself: “How did they do that? What does it take to get this sound?” Gradually I found my path, and when it happened, it all felt natural.The

The moment I sat in front of a drum machine, the moment I entered the world of sound processing, it all came spontaneously. Almost automatically, really. And that fascination has never left me. I’ve always been passionate about computers.As you mentioned, the 464 was my first “real” computer, then came the PC, and finally a laptop with a very simple editing program. I was making beats without even a timeline, just cutting and pasting sounds. Then software like Reason and Ableton came along, which really allowed me to combine ideas. That’s when everything changed. And I have to thank many people. People like Robert Henke at Ableton, whose abilities far surpassed mine, who created that software. It revolutionized the way we make music today. I’m grateful to those people.

You once said that chaos can be positive. Quoting Kandinsky: how do you manage the balance between creative chaos and technical discipline in your daily studio practice?

With age, and to protect faculties like hearing, you have to be more measured about the time you spend working. There were periods when, especially when I smoked a lot, I’d wake up, go straight to the studio, and just smoke, smoke, smoke. I was much more disconnected from reality, to be honest.As you grow older, and especially with children, you can’t live like that anymore. You have to find ways to… balance.Exactly, balance.

At the same time, though, I retain a huge amount of information in my head. I spend a lot of time collecting it, and when it comes time to put it into practice, I go into the studio and know exactly what to do. I also take a lot of notes: I draw small diagrams, jot down ideas, scales, anything that comes to mind.

Many times I go into the studio and actually don’t create anything finished. I’ll be there doing “du-du-du-du-du” on the sequencer, then play it, record something, leave it there, come back later, and add another layer. I build layers over time. Then I take a computer, maybe a MIDI keyboard, and give myself a break in Amsterdam for a couple of days: I bring all the recorded material with me and start really writing there.Nowadays, writing and recording are very separate; before, they were fused together, one process. Now, I write first and record later. That’s the current process.

Your sound has always been mysterious and abstract, yet never cold. How do you maintain emotion and warmth in such digital and geometric soundscapes?

Well… it’s difficult. To be honest, I’ve always loved every kind of music. When I was young, I was really into soul, R&B, and of course pop. I played the clarinet, so I listened to everything—I never closed my ears to anything, I never dismissed any genre.I think that created a kind of internal library of sounds and melodies inside me. I have countless melodies in my head, taken from a thousand records.

But when they emerge, they’re processed through an internal filter and transformed into something completely different.Yes, my music might seem mysterious, but for me, it’s just a mirror of my daily life, of my state of consciousness. It doesn’t feel mysterious to me, but I understand why it might seem so to others. And I’ve never wanted to make “genre” music. I love drum and bass, but I’ve never wanted to make it. I love jungle, but I’ve never wanted to make jungle. I love techno, but I’ve never wanted to make only techno.

I’ve always wanted my own language. Whether it’s harsh, beautiful, or abstract, it still has to make you feel something—even me. When that happens, I can let it go.I’m lucky because I have a lot of music that people haven’t heard yet: albums that I’ve been able to live with and listen to for years before releasing them. So when I do release something, it’s because I’ve lived with it for a long time and feel it’s the right moment. I want to release music that resonates with me. If other people like it too, that’s fantastic.

Final question. The Biennale often addresses themes like future identity, crisis, and hope. What is your greatest hope today—not just as an artist, but as a human being who creates, guides, and evolves in this world?

There have been many moments when music has truly saved me. When I was going through difficult times, there was always a track that could help me get through the situation or fill a void. When the world feels tense, I find refuge in music. I’m fortunate to have it as an emotional outlet.And this is what I consider important in modern electronic music.

I believe that today, so many people make music because they need a place to hang their emotions, their questions, their philosophies. And much of this can be found through creating sounds and tones.The world has always been a complicated place, but also a wonderful one. I am always grateful to be able to experience it, truly.Regarding politics and tensions, forces constantly looming over us, that’s exactly why clubs exist. That’s why places like the Biennale exist, where we can observe ideas about the future.And that’s where hope resides.As

As long as we have spaces for discussion, art, and creativity, things will be alright. Technology will continue to advance and change us. There will always be brilliant minds, benevolent minds, and less benevolent minds; but it’s always a dance, a play of pushes and counter-pushes. It has always been like this, and it has to be like this.And in this, there is always hope. That’s where I land my plane. Very realistic.

Thank you, Actress, for being with us. Enjoy your evening in Venice, and see you soon.

It’s been a real pleasure. Thank you.